The Current State of Robot Foundation Models

Introduction

In the past 8 weeks, I’ve been reading research papers about robotic foundation models and locomotion non-stop. While my Twitter timeline every day is spammed with impressive demos, there is a general trend that I’m noticing with progress as well as lessons that we’ve learned from language models that can guide our research on robot foundation models moving forward.

In this blog I won’t be going over all the seminal papers1, but rather comment more on the general trends as well as where we can focus our efforts towards building general purpose robot foundation models, also known as the API for physical control2.

Generalist vs. Specialist Models

In the early days of language modelling, many research efforts were focused on building the best translation or poetry models. Until the Sentiment Neuron paper led by Alec Radford demonstrated how training a model on millions of Amazon reviews via next character prediction has emergent capabilities that are downstream of the loss function like sentiment analysis.

This motivated scaling both the amount of data and size of models to train on much more generalized datasets like the whole internet that led to GPT-3 outperforming all specialized models on downstream tasks.

We’re now seeing sparks of that with projects like RT-1 model from Google that shows that scaling data quality and quantity improves generalization. Another example is the OpenVLA project that was trained on 970,000 demonstrations from the Open X-Embodiment Dataset (same dataset used to train RT-X) and open sourced it – which took inspiration from the mixture of experts architecture in LLMs and added a small action model that can run in real time.

Not only did OpenVLA generalize well, but it also outperformed models 7x its size RT-2 (which is 55 billion parameters). Something we’ve seen before with LLMs like LLaMa, Mistral, and DeepSeek.

These experiments together established a somewhat baseline architecture among the frontier robotic foundation models with a VLM backbone and action policy (with some differences of using diffusion or action-chunking) as an attempt at having a System 1/System 2 architecture to solve Moravec’s Paradox.

So a key question to ask when training the next frontier models is to capitalize on these lessons and reach for generalized competent models:

How can we generalize learning in terms of data and tasks?

Cross-Embodiment

This is along the research direction of generalized models beat specialized ones, and intuitively it makes sense.

Merging datasets from different robots helps with generalization as shown with RT-X. Now it might not necessarily be the case that although a humanoid robot can learn from a quadruped robot, that it is the most efficient use of compute to train on that data.

However, even for humanoids themselves deploying a learned policy to a million embodiments might not directly perform as expected. Therefore thinking about randomizing the data collected or the hardware representation itself can boost generalization performance.

We’ve also seen evidence of transfer learning from navigation like autopilot data to robot manipulation which can improve generalization and help solve the data bottleneck.

Chain of Thoughts and Reasoning

Incorporating chain of thoughts and reasoning into the VLA models helps the models with planning actions and tasks which is essential for a general purpose robot, as demonstrated with π-0.5 or HiRobot from Physical Intelligence:

We’ve seen this play out already with the o-series models from OpenAI where models that can reason and think through before making decisions or answering questions can outperform models that don’t.

This will become much more evident in robotics when they’re working on long horizon problems like “Cook a Margherita Pizza” that involve multi-stage complex planning and observations.

Benchmarks

Interpretability and performance measurement is still an open and unsolved problem with language models, with some interesting work like the ARC benchmark or the LLM leaderboard as proxies to generalization measurement.

However robotics face additional challenges beyond just generalization measurement, they take much more time than the average llm bencmarks3 because of complexity of taking actions in the real world. This inherently makes it testing small ideas harder, and justify building infrastructure around simulation evals.

Nevertheless, robotics benchmarks are much far behind LLMs. Some interesting under-explored areas for benchmarking abilities is in a curriculum (i.e. gradual difficulty increase).

So far LIBERO is a popular benchmark in robotics, which is basically a dataset to train on for imitation learning on four different types of tasks to test on and compare results with.

My favourite kind of benchmark is the Fiver benchmark, whether its for LLMs or robotics. Deploying in the real world is by far the best way to measure performance via actual utility. For example, UniTree running a marathon with humans is the ultimate measure of algorithms and hardware altogether (generalization, battery life, randomness, etc)!

The importance of evaluations here can be in practice much more important and severe than in the LLMs case, that is imagine the digital brain of humanoid robots being updated with the wrong software suddenly across the world. Imagine how many things can go wrong?!

Some alternative approaches to simulators is using World Models, just like organizations like Wayve or Comma AI use them for training on-policy autopilots they could be used to test control policies.

Some metrics or things to think about when designing robotic benchmarks:

- visual/instruction generalization of VLMs

- action generalization (different initial positions, types of objects, etc)

- learning new representations for diverse scenarios

- long horizon dexterity like preparing a salad

- embodied reasoning benchmark from google (trajectory, action, spatial)

- cross embodiment performance

- constitutions for safety like the Asimovbenchmark from google

- distribution of tasks, difficulties, lighting conditions, and so on

- how fast can it adapt to learn new things

Humanoids are the ultimate benchmark for embodied AGI because of the diversity of problems to solve, and we can benchmark against humans performance. Also, they provide the most amount of economic value.

Scaling Laws

LLM training has advanced a lot thanks to the scaling laws for both training and inference, but we’re no way near solving this in robotics yet. I think the research community is definitely scaling pilled now and have internalized the bitter lesson, but unlike text we don’t know how to use more data yet.

For example, this is some task performance benchmarking for Gemini Robotics. As you can notice from the figures, some tasks we’re overfitted and performance was dropping with more demonstrations.

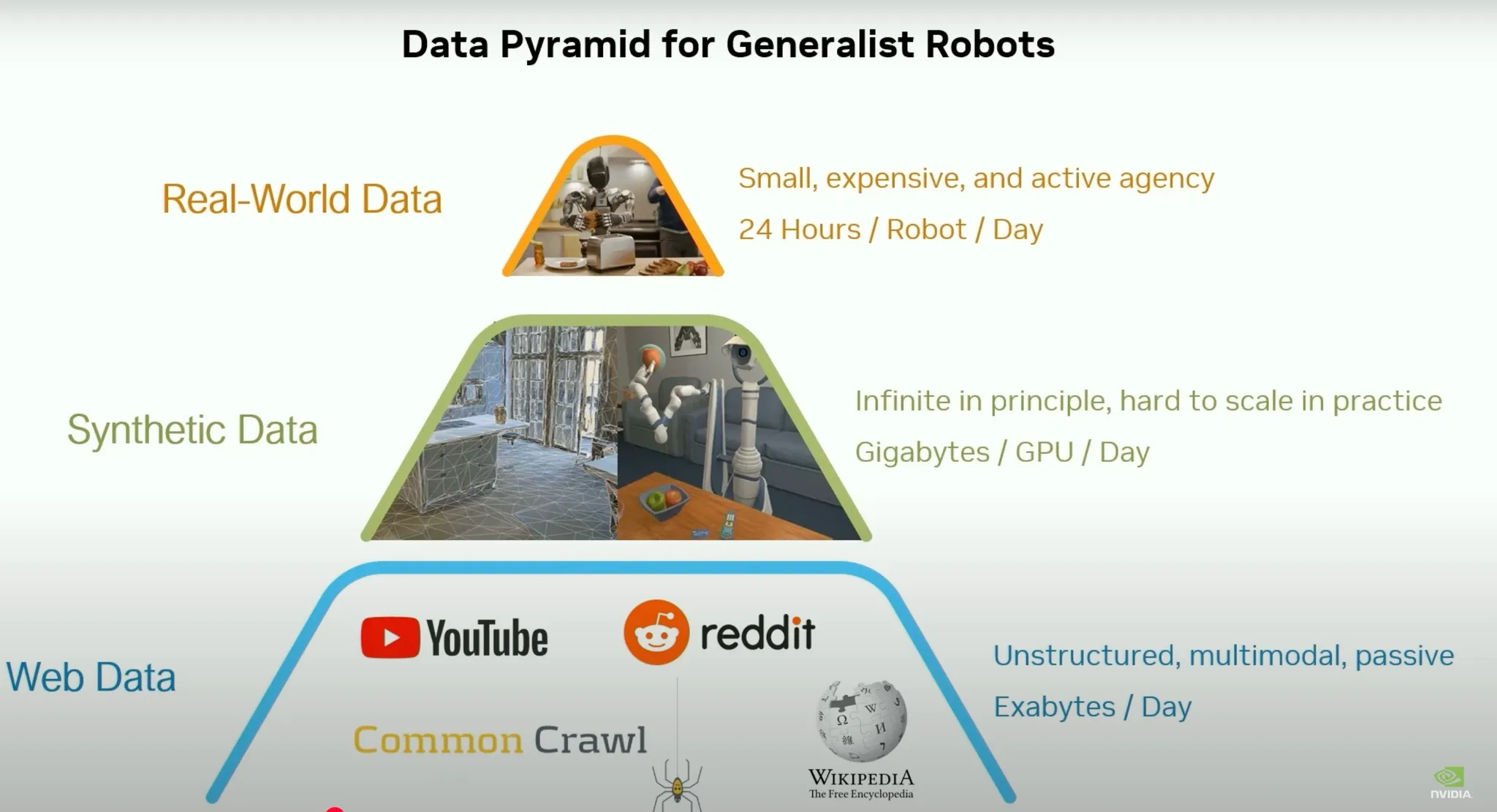

The Data Pyramid

In the 2025 Nvidia GTC, Jim Fan along with other researchers/engineers that worked on GROOT gave a talk about the data pyramid behind their GROOT model:

Since we’re bottlenecked on robot data, figuring out ways to re-purpose internet data and learn from simulation will be critical to build generalized robot models.

Gains from innovation on leveraging World-Models and synthetic data from SoTA image/text/video foundation models is one way to solve it.

Improving simulators themselves for parallelized training and benchmarking can improve the speed of the data flywheel.

Hacking Loss Functions vs. Generalization

Another trend that I’m noticing in the robotics research community is the continuous effort to beat benchmarks and metrics in specific domains like Dexterous Manipulation or Bipedal Walking.

I think it’s already been made very clear that we can learn complex skills if we try hard enough (AlphaGo, MuZero, AlphaZero, Diplomacy, etc) the question is how do we generalize learning and use RL to become world class for the physical world?

We’ve already seen excellent projects that use some form of reinforcement learning to solve dexterity like the RoboPianist that uses RL to learn how to play the piano, or Eureka that utilizes GPT4 to write rewards to learn different types of tasks like spinning a pen with one hand.

However, we have yet to see a generalized policy that can learn all forms of manipulation as part of a Vision-Language-Action model. The Figure demo of two robots cooperating together near the fridge is an excellent example of this.

What I dislike about approaches like AnyDexGrasp is although they can beat benchmarks and improve accuracy by a lot, they’re not tailored towards generalization learning. For a given amount of compute, we can fit different architectures to solve different problems, but I think best place to allocate researchers time and resources should be on generalized learning that if shown successful in manipulation can be transferred to walking and so on.

Fine-Tuning

Major progress in deep learning has been in the form of research gains in terms of compute multipliers, optimization and regularization (think DropOut, skip connections, etc) that although didn’t directly solve generalization, have made training far more efficient and scalable.

In LLMs, the research community has established very robust libraries for fine-tuning like LoRA and for distilling knowledge into smaller models.

Some examples of this in robotics is OpenVLA-OFT from Chelsea Finn’s team that showed a 25-50x speed up in inference and 20+% in performance boosts, or SOAR from Sergey Levine’s team for autonomous instruction following skills. Low hanging fruits like this can make huge impacts to the data training flywheel.

Establishing Software and Hardware Baselines

In robotics, unlike LLMs a lot of our code is deployed into the physical world. ImageNet really helped establish a baseline for researchers around the world to work on training algorithms for image classification and compare performance with others.

Robotics on the other hand, has far less well constructed datasets, and hardware is far more diverse. However there have been some interesting work recently published that can help unify the efforts of robotics researchers and engineers around the world to use as baselines and compare results much easily.

Some examples of this is the Ruka Hand or LeRobot from Hugging Face. In the field of humanoids, UniTree seems to be the most open source high quality platform in terms of both their hardware and software, open sourcing manipulation datasets and becoming a defacto go to at the top robotics labs in order to do robotics research.

Other important efforts like this are the Mobile ALOHA or Fourier ActionNet Dataset which are very useful for the entire research community to improve training the next OpenVLA.

Safety and Adversarial Attacks

Right now, because of market dynamics competition, power laws of VC investments, the Tesla approach of (expensive, moderate, cheap) cars and winner takes all — companies are rushing to deploy humanoid robots in 2025 into homes.

So far, people are welcoming robots with excitement — and who wouldn’t? But emotions aside, I think we’re increasing the odds of a dark Black Swan event. It will be necessary that these robots can’t get instructions from the internet, nor be hacked together. Most importantly, they should never be able to be manipulated into hurting someone.

Adversarial attacks to VLMs (and by extension VLAs) represent huge vulnerabilities. Safety from physical harm and attacks is still far behind capability research. VLMs can be data poisoned and manipulated to perceive different things relatively easily.

Robot Character

Finally, as robots get deployed more into the real world and become part of our daily life, it’d be nice to get them to have characters that integrate them properly into our society.

Disney research for example has done some impressive research work on integrating fun emotions, expressions, and feelings into human-robot interaction. They collect demonstration’s and reward models via RL to walk in a cute funny way. Also, tools from Boston Dynamics around robot aesthetics, or Universal Studios putting dragon costumes on Boston Dynamics quadruped robots make them much more fun to interact with.

1X afaik might be the first robotic company to explicitly hire for a robot character engineer in fact!

Some open problems listed on their job opening:

- How would you extend a realtime audio conversation agent to do co-speech gesture generation?

- Motions for nonverbal communication (e.g. emoting) are usually treated separately from task completion behaviour (e.g. folding laundry). How would you merge the two together?

Conclusion

While this is not a complete list of all trends around robot foundation models research, I hope that they inspire researchers and engineers to think about ways to leverage progress in LLMs as well as direct their research towards generalization instead of beating narrow task benchmarks.

Notes

-

Toward General-Purpose Robots via Foundation Models: A Survey and Meta-Analysis ↩

-

“A read/write API to physical reality”, Eric Jang ↩

-

read the “How to Speed Up Evaluation” section for a detailed discussion about the challenges of benchmarks for robots ↩