Moravecs Paradox: Spelled Out with Code

Introduction

In 1988 Hans Moravec1 wrote a book: “Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence” trying to forecast the AGI singularity and discuss the limitations of artificial intelligence while contrasting it with human intelligence.

In his book he made a very insightful and critical observation about the asymmetry of learning reasoning skills compared to physical skills between humans and machines2:

It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on

intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them

the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility.

At the heart of this observation, is the idea of reverse engineering sensory and motor skills being a challenging endeavour2:

Encoded in the large, highly evolved sensory and motor portions of the human

brain is a billion years of experience about the nature of the world and how to

survive in it. The deliberate process we call reasoning is, I believe, the thinnest

veneer of human thought, effective only because it is supported by this much older

and much more powerful, though usually unconscious, sensorimotor knowledge. We are

all prodigious olympians in perceptual and motor areas, so good that we make the

difficult look easy. Abstract thought, though, is a new trick, perhaps less than 100

thousand years old. We have not yet mastered it. It is not all that intrinsically

difficult; it just seems so when we do it.

While reading the recent robotic foundation models research papers and observing the general architecture of the frontier3 models like PI from Physical Intelligence and GROOT from Nvidia, as well as companies building humanoids in the real world like Figure with Helix – it becomes evident that it’s very important to understand this dichotomy, as a giant clue to the problem of how to construct an intelligent model to learn these sensorimotor tasks in terms of data, architecture, and algorithms.

All the things that humans were considered to be smarter at like Chess or Go, AI is now smarter. Robots, unlike LLMs can’t afford to complete tasks only 95% of the time or finish 95% of the task at hand in order for them to be useful in the real world and win the pockets of consumers.

The biggest consumer robotic companies in the US to date are probably iRobot for mopping floors, Amazon warehouses robots, Boston Dynamics Spot for site exploration, as well as Tesla with FSD. In all these problems, robots must get it right 100% of the times and can’t have human in the loop as supervisors i.e. the bar for utility is extremely high!

For robots to have their ChatGPT moment, and have general purpose robots4 deployed at scale in different segments of the economy we must solve physical intelligence.

Humans go to university for four years to get a CS degree to learn how to program computers, but never go to university to learn how to pick and place a glass cup. Yet today we’re able to train an LLM to achieve human level performance in coding in the matter of months, but still haven’t cracked how to have a general purpose robot catch a flying baseball or manipulate small objects like threading a needle or picking up a paper clip.

Manipulation is indeed difficult, but intuitively it feels like being able to pick up objects and transport them is not as impressive as being able to reason through solving math problems or create Ghibli style images from text.

In this essay, we will discuss some of the differences between human and machine intelligence when it comes to the physical world, apply it to a real world example (OpenAI trying to solve rubik cube with robotic hand), and explain with code two dimensions for Moravec’s paradox: learning and action.

Physical Intelligence

Neural Compute for Manipulation

A surprising fact that I learned while doing research about this topic, is the magnitude of the scale of difference in the computational resources allocated toward controlling our hands and fingers compared to the rest of our body.

The following is an illustration of the Cortical Homunculus5 ghiblified, which shows the size of each human body part proportional to the amount of neurons allocated to them. Sensorimotor control are actually much more neural compute intensive than people realize.

While this might still not be very convincing evidence as to why manipulation is hard, you can read papers building foundation models for manipulation like Mobile ALOHA and look at the scale of data used in order to learn certain tasks (on the order of 50 demonstrations per task).

But to get a better feel for this problem, check out this video recorded by Eric Jang opening a package in something like 14 steps, which just shows the amount of motor intelligence that we just take for granted.

Thinking Fast and Slow

Intelligent and flexible robotic systems not only need to perform dexterous tasks, but also understand their environment and reason through complex multi-stage problems.

Daniel Kahneman described two different thought modes that people use to solve problems, which he dubbed as “System 1” and “System 2.” System 1 is fast, instinctual and automatic; System 2 is slower, deliberative and conscious.

Figure hinted at this when presenting their Helix VLA (vision-language-action) architecture in their blog, which is built on top of the architecture of OpenVLA.

Cooking a new dish is System 2: that’s the little voice you hear in your head thinking about adapting your policies. When you do something for the 100th time, that’s System 1: it feels automatic and you hardly think about it.

There seems to a convergence towards this System 1&2 architecture with the SoTA robotic foundation models being built by the frontier labs like Physical Intelligence or GROOT from Nvidia, which could be a promising indicator the same way the attention mechanism was established by all frontier labs for training their unsupervised models for text/images.

The VLMs (vision-language models) are pre-trained internet-scale models that provide general understanding, and the diffusion part is the system 2 where most of the training is done now to solve embodied intelligence.

Control vs. Planning

Planning6 is a critical component of building general purpose robots, and robots use planning for all kinds of things like: task planning, motion planning, and path planning.

Since planning is a proxy for complex reasoning, and as we’ve already established current LLMs of today have fairly solved that – learning controllers is by far the most complex and remains the greatest barrier for making general purpose robots.

Frontier models like HiRobot from Physical Intelligence have integrated the chain-of-thought thinking of LLMs into VLAs, whereas creating effective motor control policies to this date remains the main constraint limiting progress.

We might have a lifetime opportunity to replace all kinds of classical controllers in the real world once learning generalized controllers for under-actuated systems and high degrees of freedom robots. For example, Boston Dynamics is doing very impressive work on adding RL learned controllers to replace different parts of their decades built Model-Predictive Controllers (MPC) to solve nonlinear dynamics control problems like walking on a slippery slope.

Cognitive Gaps between Human and Machine Intelligence

Beyond control and the architecture of the brain, there are some critical cognitive and physical gaps between humans and machines when it comes to decision making and learning that should be accounted for when designing embodied learning models for the physical world.

1. Qualitative vs. Quantitative Decisions

Humans make decisions qualitatively for the most part, whereas machines and computers perceive the world in quantitative measures. Therefore, in order to teach a bipedal robot how to walk for example we set proxy rewards like gait position or balance, but what reward can we give for a manipulation task like cleaning the dishes until they smell nice?

How can we describe certain behaviours and morals in numbers like drive slowly next to children even if they’re far away or describe what a neat room looks like? In games like Go or Atari it is relatively easy to describe what a winning game looks like.

We can take advantage of VLMs to do this but certain tasks are fundamentally so much harder to quantify a goal for than others, and might be solved through demonstration collection only.

2. Asymmetries in Learning and Action

We judge robot locomotion by human standards: we find a quadruped backflip way more impressive than a walking one.

Whereas in reality, a backflip is super easy to code: you just need to initially make the right lift force and there’s not much else to it. Whereas in the walking case, you need proper state estimation, filtered IMU signals, and so on to make it stable.

Balance is super easy for us and we learn it initially at a young age. Babies barely fall and learn how to walk very efficiently and have amazing mechanisms to recover.

When someone is trying to kick a robot to knock it off, the robot can compute directly in milliseconds when you’re going to hit it. Machines compute much faster and have faster reflexes.

3. Unconscious Thoughts

As discussed in the introduction of this blog, humans do not know what they are doing when it comes to control. We don’t measure or think in terms of trajectories of the things we’re doing, or how we control our tongue or fingers to do things.

We don’t remember a thing about the whole actions we do, we do them very fast like picking an apple and our hands adapt quickly.

4. Abstract Language and Actions

Our language is extremely abstract. We don’t have specific words to describe actions in physical tasks and we never needed them. For example we say spread the butter a little more, but it is not easy to describe what little means in this case and translate that to robots.

We did not need to develop language to describe more actions. We can take simple ideas and are able to abstract it quickly. Our language has a limited coverage in physical world.

Physical skills in humans heavily rely on subconscious actions that we do not understand well.

In order to build truly functional manipulation capability, we need to develop a new physical intelligence layer to ground the existing AI models to the real world.

Case in Point: Solving Rubik Cubes at OpenAI via RL

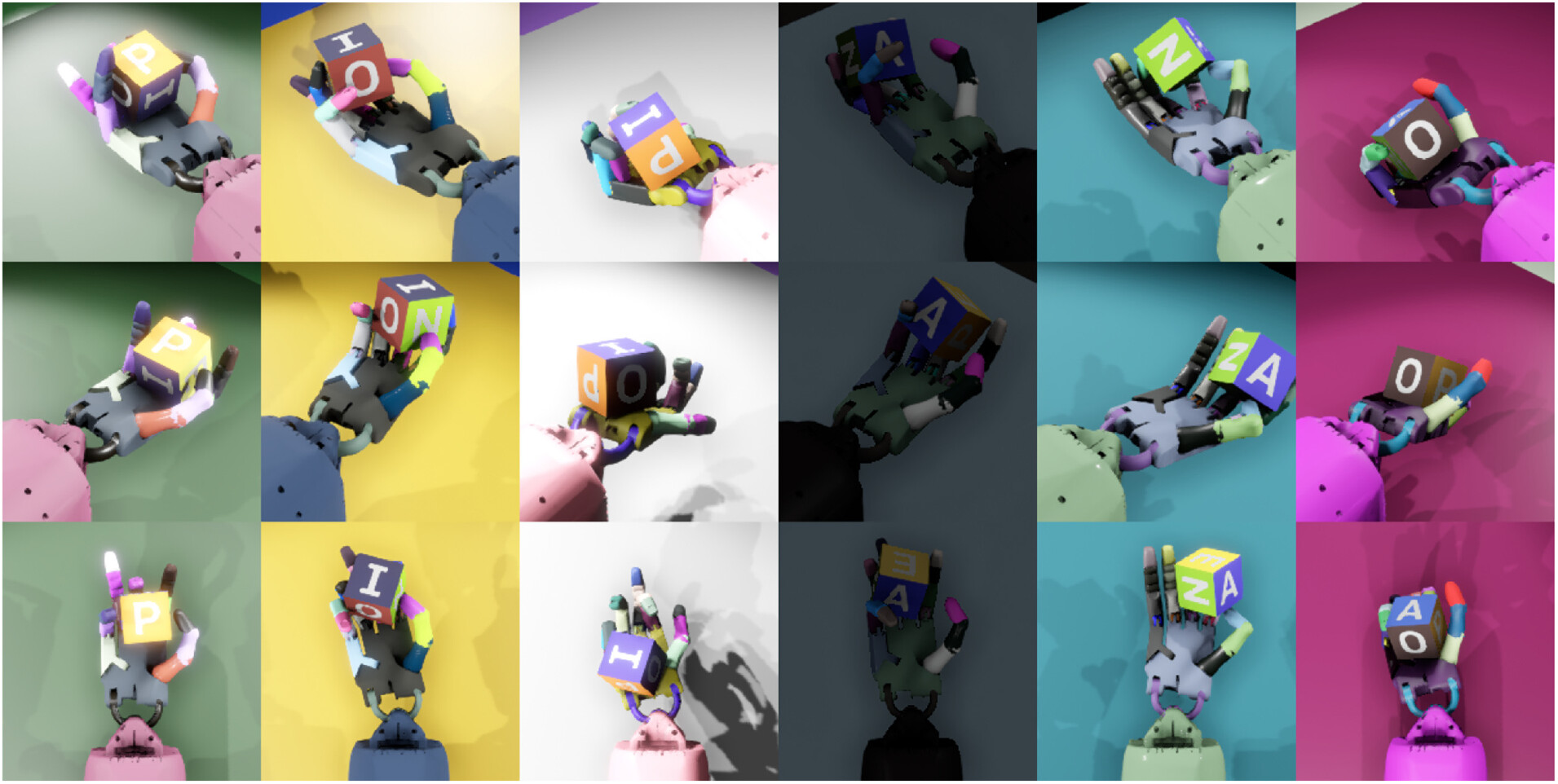

In 2018, OpenAI set out to solve the Rubik cube problem as one of their first attempts at solving AGI in their work “Learning Dexterous In-Hand Manipulation”7.

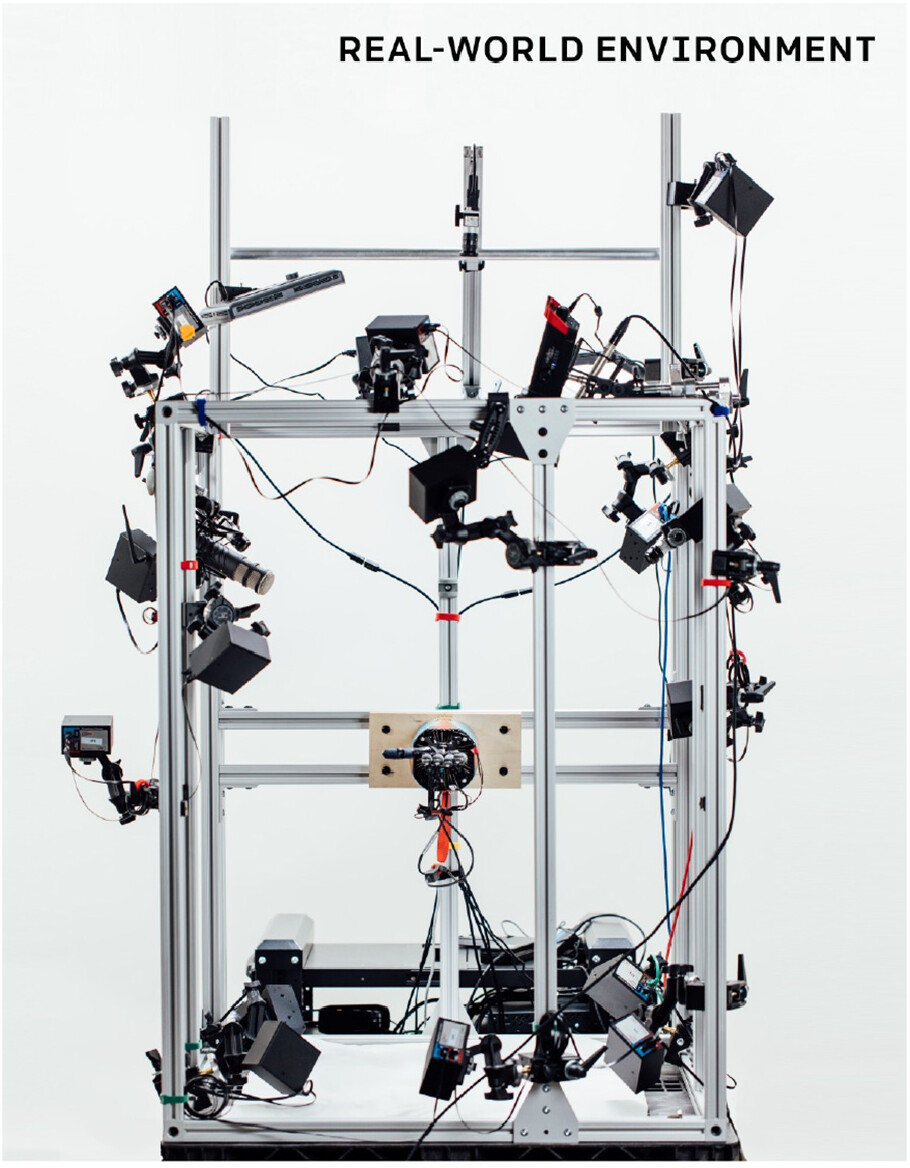

In order to bring the learned action policy into the real world to test, it required a complex behind the scenes setup (that perhaps might not all be necessary today) that had 16 PhaseSpace tracking cameras, and 3 RGB cameras which is a total of 19 cameras:

The setup used in the real world uses a:

- Shadow Dexterous Hand: a human-like robotic hand with 24 degrees of freedom controlled by 20 tendon pairs. It uses electric motors to move, with 16 independent movements and 4 pairs of linked finger joints.

- PhaseSpace Tracking: a precise 3D tracking system using blinking LED markers and 16 cameras arranged around the hand. It can track finger positions with less than 20 μm error at speeds up to 960 Hz.

- RGB Camera System: 3 Basler cameras (640×480 resolution) positioned about 50 cm from the hand. These are used for vision-based tracking of objects being manipulated, as an alternative to the lab-based PhaseSpace system.

Observations

Now let’s make some critical observations about this project as a benchmark to get an idea of what learning a physical complex reasoning task in the real world looks like:

- Task Decomposition: unless you read the paper you might not know that they used a pre-existing solver (Kociemba’s algorithm) to determine the sequence of moves, and used RL to learn physical manipulation.

- Sim2real Gap: I’ve written about this in detail here, but they had to do lots of domain randomization and curriculum learning (i.e. treating learning like a video game and making it harder as the policy learns more) in order to bring the learned controller into the real world.

- Compute: although undisclosed, it’s equated to 13,000 years of simulated experience.

- Success Rate: the hand achieved 60% success rate on average scrambles (15 moves) and 20% on the most challenging scrambles (26+ move). Note that the main failure reason was dropping the cube and not the ability to solve the problem!

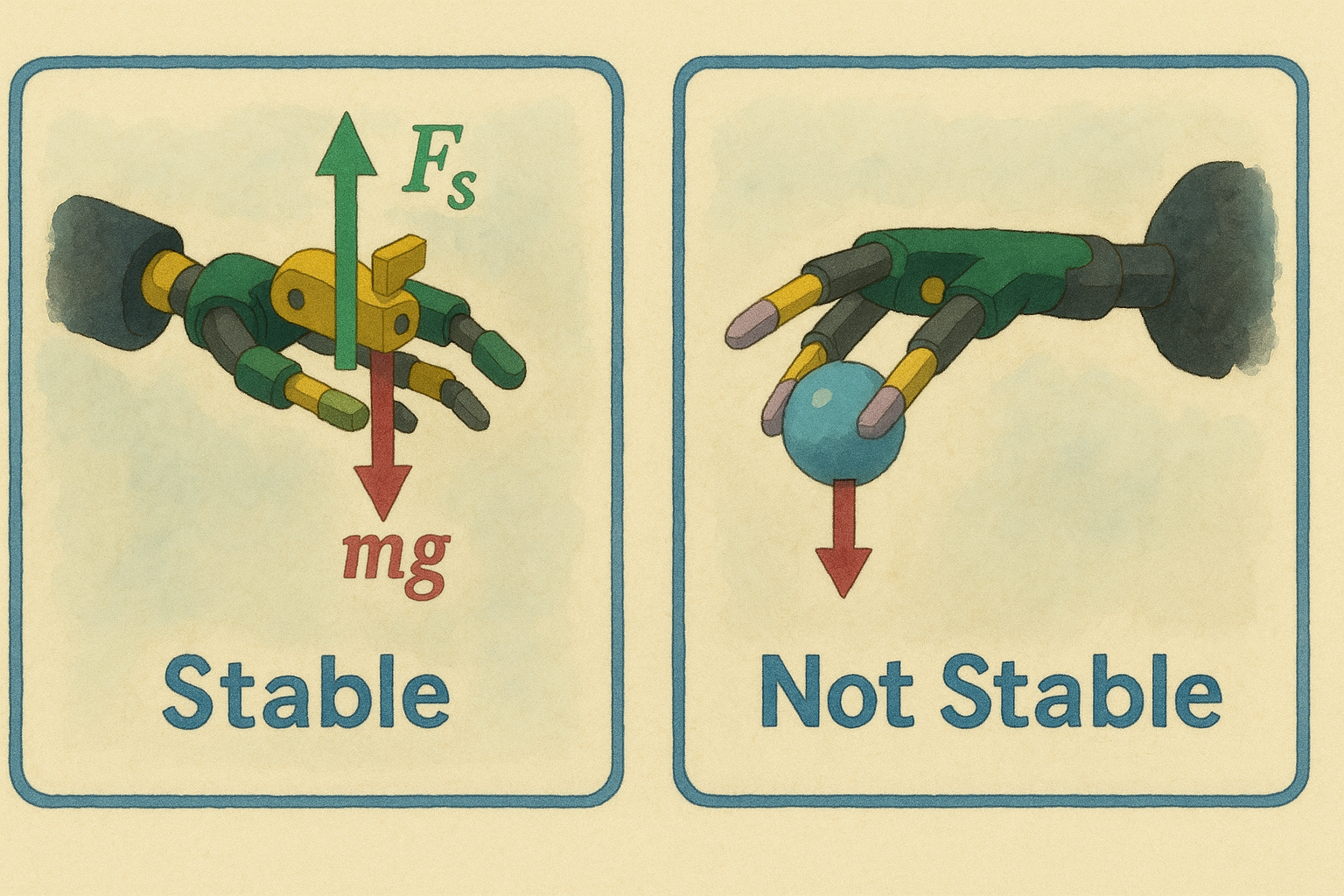

- Hand Facing Upwards: all of the hands at the time were faced upwards i.e. the object is supported by the hand which is much simpler than if the hand was facing downwards which would completely alter the physics of the problem and the learned control policy would most certainly fail in the real world in the diametric symmetrical pose.

While the research community has advanced a lot since then, I think that this is still a very good example to demonstrate the learning gaps in the physical world.

Learning via Trial & Error and Learning from Demonstrations

Now that we’ve covered what Moravec’s paradox is and discussed a lot about the differences between digital and physical intelligence – let’s dive into some examples with code!

Just like you need to feel the AGI, let’s try to feel the embodied VLA models and see what it feels like to both learn and act in the physical world using reinforcement learning as well as imitation.

We will cover the two parts of embodied AI which is to learn and act, and provide examples.

Learning

To date, most of the learning algorithms for physical tasks can be summarized into two broad approaches:

- learning via trial and error via RL like bipedal walking or backflips

- learning from demonstration via imitation learning like VLA foundation models for manipulation

1. Learning via Reinforcement Learning

The power of reinforcement learning for robotics locomotion stems from a few key points:

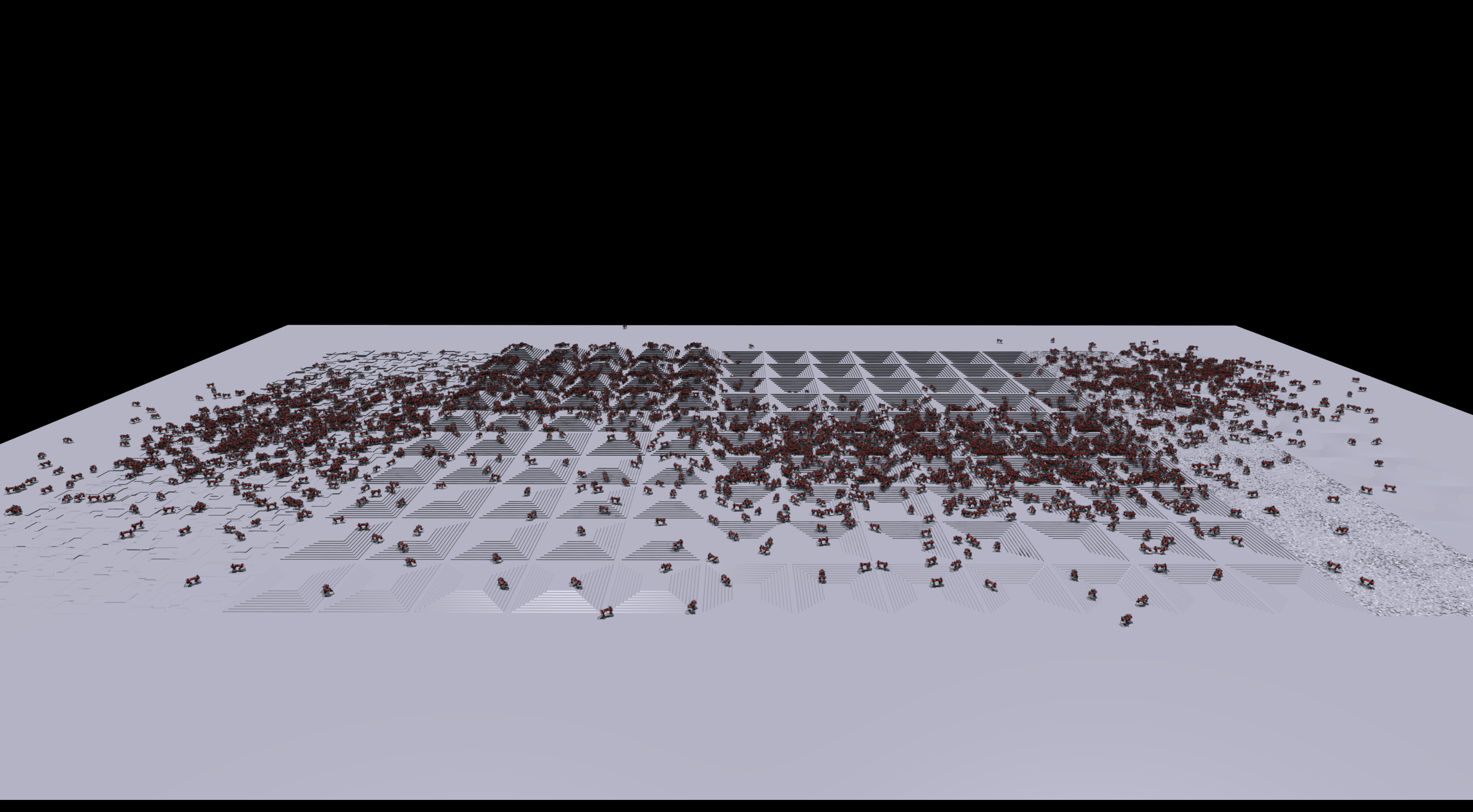

- Learning Parallelization: platforms like Isaac Lab from Nvidia have built very effective physics-based simulators that allow running RL training jobs in parallel and utilizing GPUs for learning parallelization. In other words, we’re able to compress 5,000 years8 of human locomotion into an hour in a simulator.

- Trial and Error: just like humans learn effectively by just trying the task, RL is the best approximate learning approach we have to encode that in artificial learning.

We will now cover how a complex task for humans which is doing back flips and show how easy it is to teach a quadruped robot to perform, whereas walking on diverse terrains is very easy for humans but requires extensive training and domain randomization9 for robots to master.

Quadruped Backflips

Contrary to humans, it is relatively easy to teach a quadruped robot to learn how to do a 360 degrees backflip using RL. In essence, we just need to start with the right initial lifting force by the four legs to create the rotation motion and just wait for the robot to land on its feet again and stabilize.

In fact, this is a very simple way to frame the RL problem for backflipping in python:

class QuadrupedEnv(gym.Env):

def __init__(self):

self.gravity = -9.8

self.state = np.zeros(12) # position, rotation, velocities, joint angles

self.goal_rotation = 2 * np.pi # Full backflip

self.action_space = spaces.Box(low=-1.0, high=1.0, shape=(6,), dtype=np.float32)

self.observation_space = spaces.Box(low=-np.inf, high=np.inf, shape=(12,), dtype=np.float32)

def step(self, action):

# Physics simulation

self.state[4] += np.sum(action) * 0.5 if self.current_step < 10 else 0 # Jump impulse

self.state[5] += (action[0] + action[1] - action[2] - action[3]) * 0.2 # Rotation

self.state[2] += self.state[5] # Update rotation angle

self.state[4] += self.gravity * 0.1 # Apply gravity

# Reward function

reward = min(1.0, abs(self.state[2]) / self.goal_rotation) # Rotation progress

+ min(1.0, self.state[1] / 2.0) # Height

- 0.01 * np.sum(np.square(action)) # Energy efficiency

+ (10.0 if abs(self.state[2]) >= self.goal_rotation else 0.0) # Success bonus

done = self.current_step >= 100 or abs(self.state[2]) >= self.goal_rotation

return self.state, reward, done, False, {}

# Train with PPO algorithm aka where learning happens

def train_backflip():

model = PPO("MlpPolicy", QuadrupedEnv(), verbose=1)

model.learn(total_timesteps=10000) # Robot learns through thousands of attempts

return model

where we basically reward the robot positively or negatively based on how well it performed on rotation, height, energy consumed as well as how complete the backflip was:

reward = rotation_reward + height_reward - energy_penalty + success_bonus

And that’s it! This could take several minutes in a parallelized Isaac Lab environment to learn and the robot could flip as fast as the best human athlete!

If you want to read a nicely well written paper with code for learning more about training quadruped robots for walking, check out this paper from ETH Zurich: “Learning to Walk in Minutes using Massively Parallel Deep Reinforcement Learning” that also includes code for legged gym environment.

An observation from this paper that is relevant to the power of using simulation to do RL based learning is doing domain randomization like changing terrain types:

- Randomly rough terrain with variations of 0.1m

- Sloped terrain with an inclination of 25 deg.

- Stairs with a width of 0.3 m and height of 0.2m

- Randomized, discrete obstacles with heights of up to ±0.2m

This effectively would be much more time consuming to replicate in the real world. In this work, they were able to train an effective quadruped locomotion policy in under 20 mins10.

2. Learning from Demonstration: Imitation Learning

There’s a strong argument to be made as to why imitation learning is very effective for robot learning and is basically the baseline approach that all the frontier robotic foundation models labs are using:

If unsupervised learning was solved via next token prediction for LLMs,

why can't the best VLA model output the best human-level actions by doing

accurate next action prediction?

The scaling laws for imitation learning11 in robotics12 are yet to be figured out, but it’s quite clear given the work on the RT-X model series from Google that scaling and collecting cross-embodiment data and other characteristics of LLM scaling laws transfer well into robotics!

The exciting fact about robot foundation model training is that we’re slightly converging into the same process taken by LLMs for training foundation models for robotics which in hindsight should be the case13.

We’re also seeing emergent properties like robot cooperations to do tasks as demonstrated by GROOT and generalization to different environments.

Bi-Hand Manipulation: Mobile ALOHA

The field of robotic foundation model training via imitation learning is a rapidly evolving field with lots of excellent work to discuss. However for the sake of this blog, we will talk about a very popular and baseline paper for imitation learning from Stanford called: “Mobile ALOHA Learning Bimanual Mobile Manipulation with Low-Cost Whole-Body Teleoperation”.

Mobile ALOHA builds on top of ALOHA (a low cost hardware aparatus) from Stanford, that introduced an affordable open source bimanual robot system on wheels and extended task range as well as learning efficiency.

The original ALOHA project provided a dual-arm design with 7 DoF manipulators, coupled with an open dataset of tele-operated demonstrations for learning from demonstrations. They also present an Action Chunking with Transformer (ACT) algorithm which has inspired a lot of the leading robotic foundation models to reduce some of the problems introduced by imitation learning like error compounding and drifting out of the training distribution.

Below is a 25‑line PyTorch sketch for what behaviour cloning looks like to train a Mobile‑ALOHA‑style policy purely from demonstrations:

import torch, torch.nn as nn

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

from torchvision import models, transforms

import h5py # ALOHA demos are released as HDF5

# ---- 1. Dataset -----------------------------------------------------------

class AlohaDemo(Dataset):

def __init__(self, h5_path, resize=128):

self.f = h5py.File(h5_path, 'r')

self.rgb = self.f['images/rgb'] # (T, H, W, 3)

self.act = self.f['actions/cartesian'] # (T, 7) ⇠ pos + ori + gripper

self.tf = transforms.Compose([

transforms.ToPILImage(),

transforms.Resize(resize),

transforms.ToTensor()])

def __len__(self): return len(self.rgb)

def __getitem__(self, i):

return self.tf(self.rgb[i]), torch.tensor(self.act[i]).float()

# ---- 2. Model -------------------------------------------------------------

backbone = models.resnet18(weights="IMAGENET1K_V1")

backbone.fc = nn.Identity() # 512‑D vision feature

policy = nn.Sequential(backbone,

nn.Linear(512, 128), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(128, 7)) # 7‑DoF end‑effector command

# ---- 3. Train loop --------------------------------------------------------

loader = DataLoader(AlohaDemo('demo.h5'), batch_size=64, shuffle=True)

opt = torch.optim.Adam(policy.parameters(), lr=3e‑4)

loss_fn = nn.MSELoss()

for epoch in range(10): # ‑‑ tiny demo, not SOTA

for rgb, act in loader:

pred = policy(rgb) # forward

loss = loss_fn(pred, act) # L2 on actions

opt.zero_grad(); loss.backward(); opt.step()

print(f"epoch {epoch}: {loss.item():.4f}")

We literally treat “robot vision → action” as next‑token prediction — exactly what LLMs do with text!

These are the results shared in the paper by training from demonstrations:

| Task | Demonstrations | Success Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wipe Wine | 50 | → | 95% |

| Call Elevator | 50 | → | 95% |

| Use Cabinet | 50 | → | 85% |

| High Five | 20 | → | 85% |

| Rinse Pan | 50 | → | 80% |

| Push Chairs | 50 | → | 80% |

| Cook Shrimp | 20 | → | 40% |

Keep in mind that these results are achieved after using a pre-trained backbone on previous demonstrations, and even with that it took 20 examples to learn how to do a high five! Whereas a five year old child masters it after watching you once!

In this example, we’ve demonstrated how teaching robots from examples looks like as well as the efficiency of these algorithms compared to human brains.

Thought Experiment

Try to manually go through a task example from the training set in a VLA like GROOT or PI-0 and plot how this instruction flows through different parts of the VLA model like tokenization of the instructions/images into the VLM backbone and how it gets converted into an action policy. This exercise should really help build your intuition to how the world is perceived by VLA models and feel the embodied AI.

Conclusion

Hopefully in this short blog, we were able to explain what the Moravec’s paradox is, the differences in learning between humans and machines in the physical world, as well as how our current state of the art learning approaches are at handling that gap!

We’ve cracked language, vision, and reasoning — but the hardest problem of all might just be: not dropping the ball. Literally.

The future of AI will depend on solving for control, not just cognition.

I hope this blog helps shed the light on important aspects of physical intelligence, as well as how we still need to focus on solving tasks with generalization!

Expect some more research from me around the current state of the art of robotic foundation models as well as the data bottlenecks soon!

Notes

-

which he wrote as part of his career as a researcher building autonomous robots. ↩

-

The real frontier isn’t in reasoning — it’s in reaching for a glass of water without dropping it! ↩

-

Moving forward, we will assume that a general purpose robot to be a robot that can do different tasks in different environments autonomously like a human. ↩

-

how much neurons are dedicated for each part of the human body. ↩

-

Planning decides what should be done; control determines how it’s physically executed. ↩

-

https://openai.com/index/learning-dexterity/ ↩

-

5,000 years as a reference to the first evidence of writing in human civilization in ancient Sumerian ↩

-

https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2019-05-05-domain-randomization/ ↩

-

I’m working on a project to use RL for bipedal walking which hopefully will be released soon, be sure to check it out for more intuition about using RL to learn action policies! ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2410.18647 ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2405.14005 ↩

-

Just like we have one brain to learn reasoning as well as physical skills. ↩