The Sim2Real Gap for Robot Locomotion Explained

Introduction

Simulators in recent years have advanced significantly, with platforms like Mujoco focusing on getting accurate physics engines to model the real world, and the ecosystem by Nvidia like Omniverse providing photo-realistic engines. These advancements unlock enormous opportunities to do lots of algorithmic robot learning for bipedal locomotion and dexterous manipulation in simulation.

Yet, when it comes to translating learned algorithms into the real world, learned policies often suffer from what is known as the sim2real gap.

In theory, anything that can be learned in simulation should be directly translatable into the real world. And for industrial companies building fleets of hundreds of robots1, it’s critical to get the sim2real gap resolved in order to iterate confidently from development to deployment.

In robotics, unlike language models, learned policies take immediate actions in the real world that can cause things to break or harm the people around them.

In this blog, we will discuss what the sim2real gap means, where it originates from, as well as some techniques to bridge the gap to maximize the upside of simulators.

Thought Experiments

Before we define the sim2real gap, I’d like to illustrate the concept with two thought experiments:

Experiment I

Suppose you walk a real bipedal humanoid robot in the real world using some control policy and record every action command taken in every motor, and then play the same actions again from the same initial position on the same exact robot. What would you expect to happen? Turns out, after a few steps the robot is going to fall!

The real world is full of noise from hardware vibration to changing physical environment, and no two runs are exactly the same. Therefore, we can’t have an exact fixed control policy running the same actions everytime, we need to adapt to the current situation based on state estimates and surroundings observations.

Experiment II

Now suppose you walk a bipedal humanoid robot inside of a simulator using some control policy and record every action command taken in every motor, and then play these same actions again in the real world with the same initial conditions. What do you expect to happen now? Like experiment I, the robot will fall except much faster this time!

Not only is the real world full of noise, but the physics inside simulators are not accurate compared to the real world no matter how good the simulators are. Things like gravity, wind, and surface friction are all hard to represent accurately.

Based on these two experiments, it is therefore a necessity to account for the sim2real gap and design control policies that are both robust and realistic.

The Sim2Real Gap Explained

In order to better understand what the sim2real gap is, one must first understand what a simulator is. From first principles, a simulator is a mapping between the current state and action to predict the next state:

The sim2real gap is the difference between what the next state inside the simulator is and the one that happens in the real world:

As illustrated in the previous thought experiments, getting an accurate state estimation in simulation that represents the real world is not feasible. The problem compounds (think integral of small noise surface areas) with every new step taken by the robot, as the learned control policy from simulation expects the next state to be something while the real world state has a different value.

There are different approaches to compensate for this sim2real gap, but the good news is that they are general in that we can apply them to different kinds of locomotion, navigation, and manipulation policies.

State Estimation and Locomotion Control

Dynamic Modelling of Robots

Before discussing techniques to resolve the sim2real gap, let’s talk a bit more in detail about the “real next state” in the diagram above. From classical control theory, in order to control robots to do things we usually need to have a dynamic model of the physics of the body we want to control as well as state estimates (think robot pose and position).

For example, the following is the dynamic model of a differential drive mobile robot:

To build a controller for the velocity of the left and right wheels we can use the following differential drive control equations2:

\[\begin{bmatrix} v \\ \omega \end{bmatrix} = \underbrace{ \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} \\ -\frac{1}{d} & \frac{1}{d} \end{bmatrix} }_{D} \begin{bmatrix} v_L \\ v_R \end{bmatrix} \Leftrightarrow \begin{bmatrix} v_L \\ v_R \end{bmatrix} = D^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} v \\ \omega \end{bmatrix}\]As you can see, in order to control vL and vR we need to have accurate measures of (v, w) which is the linear and angular velocity of the center of mass of the mobile robot.

Now if you run this differential drive model in simulation, you can perfectly measure the linear and angular velocities of the mobile robot but in the real world you won’t get accurate results due to things like:

- manufacturing tolerance errors

- noise in signals from sensors

- vibration of robots

- etc

In this case, since it’s a linear model its easy to model the dynamics of the robot. Now imagine the controller being learned for a nonlinear model, all the more reasons to get accurate state estimates and minimize the sim2real gap in order to focus on improving the learning!

Robot states are also at the heart of any robotic foundation model: that is in order for classical or learned controllers to output actions, we need accurate observations and state estimations.

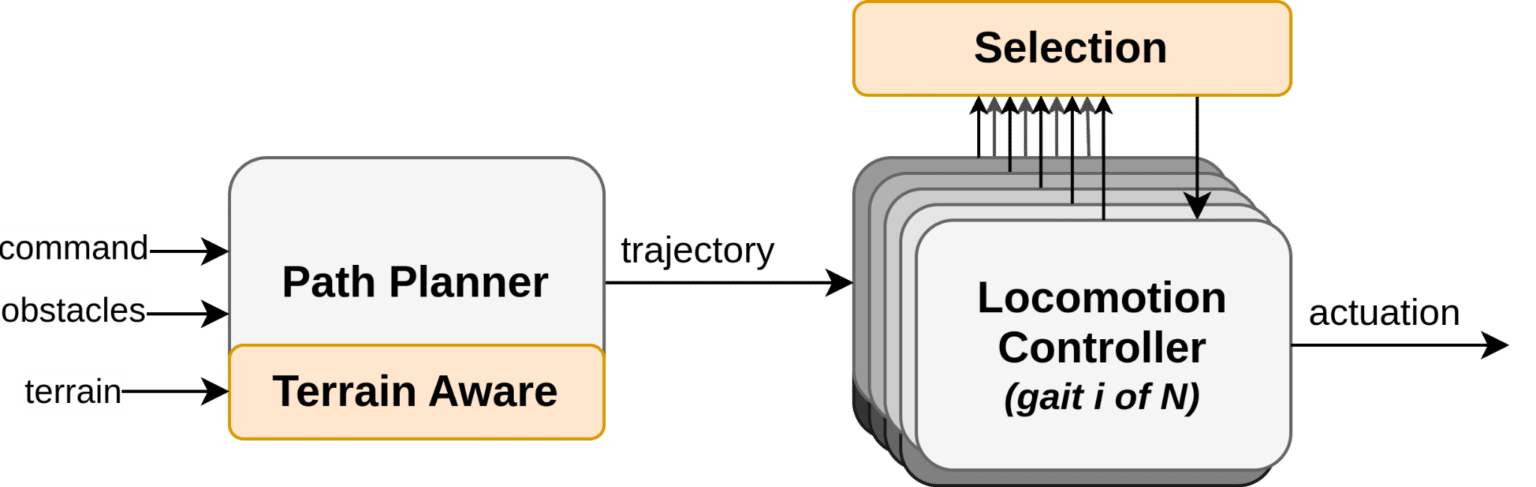

Locomotion Tuning

Getting the robot to walk before running is a necessary step for locomotion; if we want our robots to move well, we need to nail the basics first. Good movement starts with properly tuned controllers. Without this foundation, even the smartest learned controllers won’t save us.

Many teams rush to focus on fancy manipulation skills. Later, they’re confused when their robot struggles with precise movements. The problem isn’t their AI; it’s that they skipped proper movement tuning. Does your robot need to do backflips? Probably not! But it should handle stairs confidently at a decent walking pace. That’s when you know you’re ready for more advanced skills.

Now that we got a better understanding of state estimation and locomotion control, we can now discuss some of the techniques to compensate for the sim2real gap!

Techniques to Overcome the Sim2Real Gap

The best way to minimize the sim2real gap is through excellent engineering, there is no one technique that fixes it but rather a collection of things when done simultaneously with perfection add up to have a negligible gap.

1. Digital Twin in Simulation

First straightforward step is to build the best digital twin possible of the robot we’re with, that is importing the CAD design files and replicating the entire test environment the robot is experiencing in the real world.

An effective digital twin accurately represents the robot’s mass distribution, center of gravity, actuator dynamics, moment of inertia, and joint ranges of motion. The more accurate these details are in simulation, the smaller the sim2real gap will be before applying other techniques.

2. Domain Randomization

The second step is to be robust to the gap now that we know that it exists. Using techniques like Domain Randomization3, which injects well designed noise in the simulation training phase to be robust to what happens in reality.

Some projects like the Rubik Cube from OpenAI used techniques like automatic domain randomization (also known as curriculum learning) to increase the complexity of the environment as the performance of the model improves.

We won’t be going too deeply into definitions and approaches here, but if you’re interested do read Lilian Weng’s blog Domain Randomization for Sim2Real Transfer and checkout projects like Spot Quadruped Locomotion in Isaac Lab from Boston Dynamics.

3. Learning the Gap

There are many interesting approaches here in order to “learn” the gap, methods like SimOpt4, Real2Sim2Real5, and Auto-tuned Sim2Real 6 try to augment the parameters of the simulator in order to better fit reality. They work well with robotic arms but are not effective with legged locomotion.

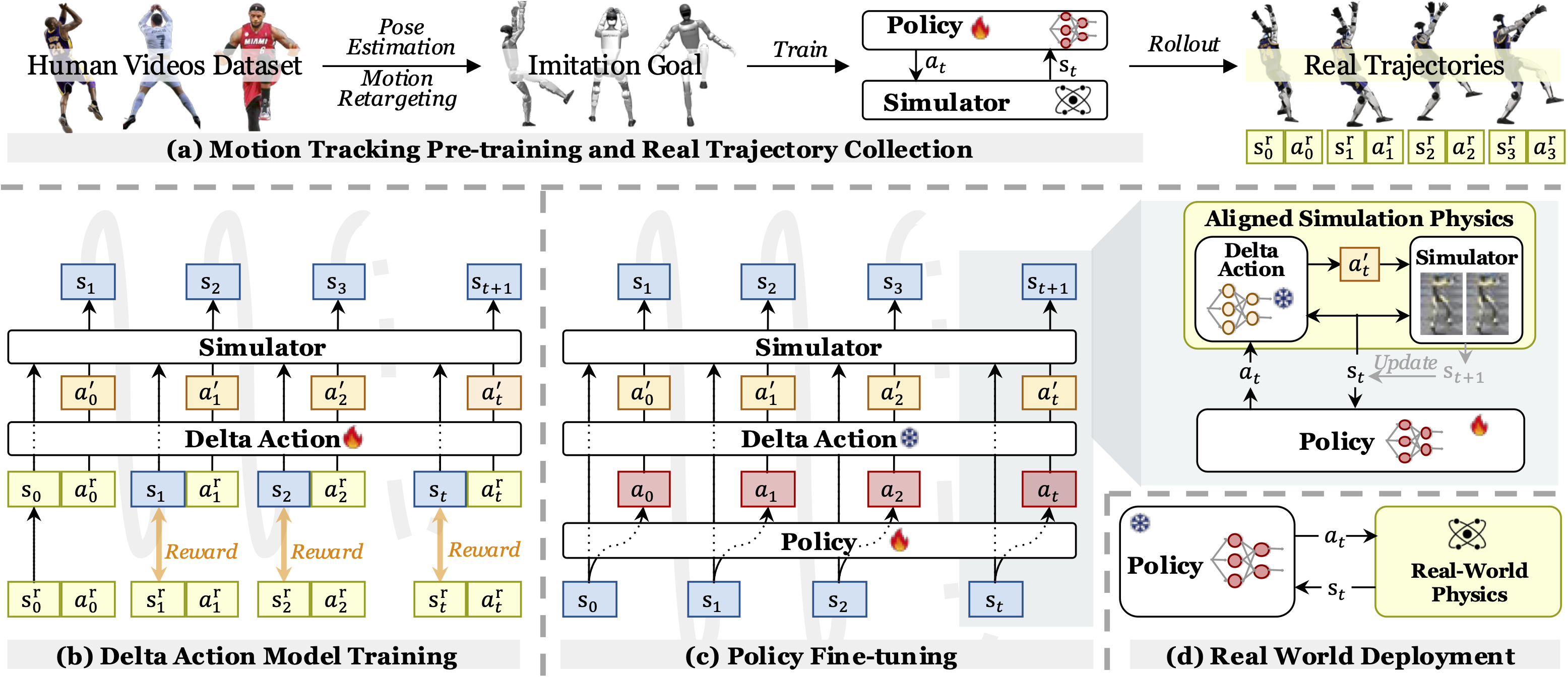

A very interesting new approach ASAP7 is to learn a corrective action policy whose goal is to adjust the original actions to the sim2real gap (basically a sim2real2sim adapter) but only applied in simulation during learning. This approach can be summarized in the following steps:

- learn action policy in simulation via RL

- deploy learned action policy in real world and collect real-world data to train a delta action model that compensates for the dynamics mismatch

- fine-tune pre-trained policies with the delta action model integrated into the simulator to align effectively with real-world dynamics

- deploy fine-tuned action policy without the delta action model in the real world

The simulator is being applied with the new action, and it is learned with the reward that minimizes the gap between simulation and reality. When we apply this corrective term we make sure that the sim2real gap becomes narrower.

They’ve evaluated performance through sim2sim and sim2real and have uncovered performance boosts!

4. Closed Loop Adaptive Controller

Another important technique is to use a closed-loop controller to compensate for errors in actuator modeling and the random noise injected from the real world by deploying an adaptive real-time controller on the robot in the real world.

Adaptive controllers are particularly powerful when they can learn and adjust in real-time. Think of them as the robot’s ability to “feel” when something isn’t quite right and compensate accordingly. Algorithms like Model Reference Adaptive Control (MRAC) or techniques that combine8 classical controllers with learned components have shown promising results in bridging the sim2real gap.

The key is finding the sweet spot between computational complexity and control frequency – a simple controller running at 1kHz often outperforms a complex one at 100Hz. If you want to learn more, check out ETH Zurich’s work on legged robots or Berkeley’s research on residual policy learning.

5. Sim2Sim Evaluation

Finally, since there’s a strong ecosystem of simulation tools each with their own set of advantages, we can test learned policies using a sim2sim approach before deploying in the real world. This allows us to build automated unit tests by creating a CI/CD pipeline of learned action policies via sim2sim.

Different simulators excel at different aspects of simulation. For example, Mujoco provides highly accurate rigid body dynamics for testing physical interactions, while Isaac Sim/Lab excels at domain randomization and photo-realistic rendering. PyBullet offers faster-than-realtime testing for rapid prototyping.

By transferring policies between simulators before real world deployment, we can identify potential failure modes that might be specific to simulation assumptions rather than fundamental flaws in our control approach.

Conclusion

Training control policies in simulation provides an incredible playground to develop algorithms that require enormous amounts of trial and error like reinforcement learning, and understanding the limitations of simulators as well as how to mitigate the sim2real gap can provide leverage to zero-shot transfer learned policies into production.

In next steps, I’m going to work on building a production grade RL controller for bipedal walking.

Notes

-

https://www.figure.ai/news/reinforcement-learning-walking ↩

-

https://www.gnotomista.com/ancillaries.html#hemingwayianunicycle ↩

-

https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2019-05-05-domain-randomization/ ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.05687 ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2111.04814 ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2104.07662 ↩

-

https://agile.human2humanoid.com/ ↩

-

https://bostondynamics.com/blog/starting-on-the-right-foot-with-reinforcement-learning/ ↩